Articles

No Comments

By Voices

On 02, Jul 2018 | No Comments | In Commemoration | By Voices

‘La Guerre des Moutons’: Remembering 1918 from 1968

Chris Hill, Birmingham City University

This year marks not only the centenary of the end of the First World War, but also the fiftieth anniversary of 1968, a year known for anti-war protests and student rebellions worldwide. From the perspective of 2018, then, the question of how 1918 was remembered during the Vietnam War and the ‘year of the barricades’ seems a compelling one.

As the British historian, Rod Kedward, has argued, the protests of 1968 and memories of the First World War often interacted in a manner that helped to mould and shape the latter: 1968 underlined the ‘futility myth’ that came to prevail in both popular and scholarly perceptions of the Great War.

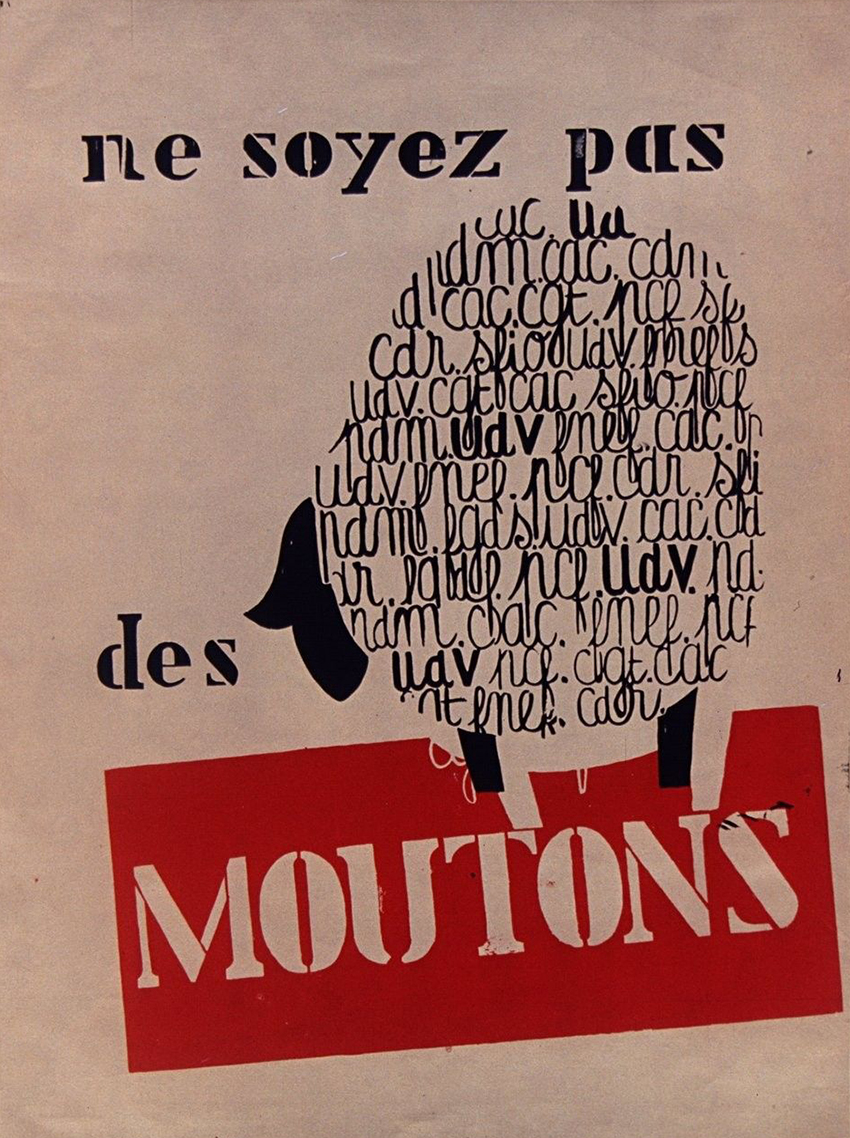

A poster from May 1968.

In relation to les événements de Mai’68, where French students and workers momentarily threatened to topple the De Gaulle government, Kedward described how protests and memories of 1918 were ‘interwoven’ on its fiftieth anniversary. This became manifest, he argued, ‘in the graffiti which began to appear on the walls in the spring of 1968, most obviously the slogan, ‘la guerre des moutons’. This ‘condemned the war of 1914-1918 as one in which men were “sent to die” by military and political authority; they were “sheep to the slaughter”’.[1]

Yet it is impossible to grasp memories of the Great War in 1968 without an understanding of how these had been mediated by the more immediate experience of the Second World War. Quite often, but for complex and wide-ranging reasons, the baby boomers of Europe distinguished between the First World War as futile and unnecessary and the Second as just and urgent. In Britain, this was expressed through cultural movements that highlighted transformations in the class system. This included the rise of documentary realism, kitchen sink drama and satire, all of which possessed an in-built suspicion of the upper middle class leadership that had marked the social structure of the British Expeditionary Force in 1914.

It was in this context that Joan Littlewood adapted The Long Long Trail, a radio production about the death of a father at Arras, for theatre; that the BBC produced its epic documentary television series on The Great War and that Richard Attenborough brought the stage-play, Oh! What A Lovely War, to cinema. As described by Martin Farr, this film ‘remains a vivid historical statement of Britain in the summer of 1968, a paean against war, popular with anti-Vietnam demonstrators on American campuses’. For Farr, ‘the film was a product of [a] spike of interest in the war, transmogrified by … effervescent London … where photographers, designers, and publicists from up and down the Kings Road were called into action’.[2]

The difference in how baby boomers and soixante-huitards perceived the World Wars was illustrated in a moment described by Rod Kedward in 1968. ‘In a small village on the Languedoc’, Kedward recalled how he witnessed ‘an astonishing public confession by a graffiti artist’. ‘At night’, he recalled, ‘the graffiti artists had decorated the Monument aux Morts with a tidily-written “guerre des moutons” only to find in the light of morning that he had covered not the side given to the First World War, but the memorial to “Nos martyrs de la Résistance” – the Resistance movement to Nazi occupation between 1940 and 1944.

The graffiti artist’s faux pas seemed to cross a fundamental dividing line in public memories of the World Wars. Whereas soldiers had been ‘sent to die’ in the First, they had fought of their own volition in the Second: the Resistance had a ‘voluntarist’ quality that appealed to the ideology of the 68ers in particular. According to Kedward, the graffiti artist later ‘came into the square as people assembled in the café for the evening aperitif and publicly announced that he had misdirected his graffiti: he had no wish to denigrate the Resistance, only the unacceptable war of 1914-18’. He went on to ‘remove the red spray paint, amidst considerable astonishment and no shortage of heckling and debate’.[3]

Through the radicalism of 1968, therefore, the meaning and memory of the First World War was re-interpreted on the fiftieth anniversary of its armistice. As Kedward pointed out, the politics of ’68 had a major impact not only on popular perceptions of the World Wars, but also on their historiographies. Reflecting on a series of academic conferences in the 1990s, he was struck by how far historians across Europe had been ‘influenced personally by the soixante-huitard perspective’.[4] If 1968 cemented the foundations of the futility myth, however, these have been chipped away at by historians today. For a perspective on war that valued agency of the individual, it is remarkable how reductive 68ers could be of the lives of 1914-1918. The task of the historian is surely not to cast these off as hopeless, but to re-discover their differences and subtleties and renew their meanings by doing so.[5]

Chris Hill, May 2018

[1] H.R. Kedward, ‘Resistance: The Discourse of Personality’, K.G. Robertson, War Resistance and Intelligence: Essays in Honour of M.R.D. Foot (Barnsley, 1999), 135.

[2] http://beyondthetrenches.co.uk/the-first-world-war-1962-69/

[3] H.R. Kedward, ‘Resistance: The Discourse of Personality’, 135.

[4] Ibid, 136.

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/jun/17/1914-18-not-futile-war

Submit a Comment