Articles

3 Comments

By Voices

On 28, Jul 2014 | 3 Comments | In Cities | By Voices

Kitchener’s New Army

Carl Chinn

By the spring of 1915, the hoardings in Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and other great cities were plentifully bespattered with Lord Kitchener’s posters calling for skilled workers to register for employment in munitions factories. One of the most striking was headed “the man the army wants now” and had an illustration depicting big guns in action with a workman engaged on a lathe in the foreground.

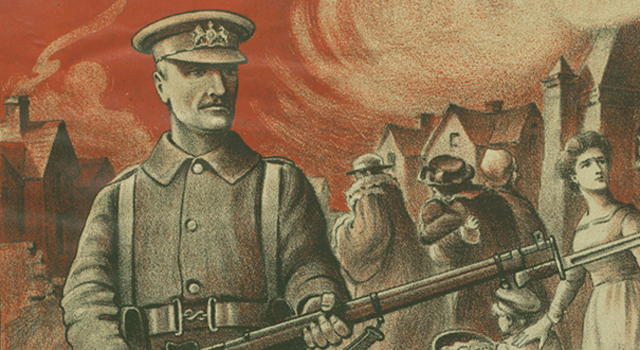

![[Library of Birmingham: LF75.12.107]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/kitchener-lf-75-12-107.jpg) Posters were as vital in the recruitment of volunteers into the Armed services. Over twenty million recruitment pamphlets and leaflets had been printed by early April, whilst almost two and half million copies of 90 different posters had been put up. For all that, surveys showed that few read the pamphlets and leaflets, preferring to find information in their national or local newspaper; however, there was no doubt of the impact of the poster campaign. They included ‘Another Call’, showing a khaki-clad bugler with Lord Kitchener’s demand for “More men and still more, until the enemy is crushed”. Another poster was illustrated with map of the United Kingdom in grey. Across it with words in red was the appeal “Britons! Your country needs you.”

Posters were as vital in the recruitment of volunteers into the Armed services. Over twenty million recruitment pamphlets and leaflets had been printed by early April, whilst almost two and half million copies of 90 different posters had been put up. For all that, surveys showed that few read the pamphlets and leaflets, preferring to find information in their national or local newspaper; however, there was no doubt of the impact of the poster campaign. They included ‘Another Call’, showing a khaki-clad bugler with Lord Kitchener’s demand for “More men and still more, until the enemy is crushed”. Another poster was illustrated with map of the United Kingdom in grey. Across it with words in red was the appeal “Britons! Your country needs you.”

But the most iconic and successful of the posters was the one which featured Lord Kitchener’s face and upper body. Distinctive with his military hat and thick, black handle-bar moustache, he glared sternly across the land. With his right-hand index finger pointed out almost accusingly to able-bodied men, he scarcely needed to command “I want you”.

According to the ‘Edinburgh Evening News’, by early July 1915 over half a million posters had been distributed around Scotland alone and “the famous finger of Lord Kitchener has prodded more men into the Army than the War Minister knows about”.

![[Library of Birmingham: WW1 Posters]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/kitchener-ww1-poster.jpg) Indeed one Edinburgh lad joined up because the poster “haunted” him and he could not get away from Kitchener’s finger. Similar feelings welled up in young men in the west midlands. Edward Rowbotham was a Black Country veteran of the Great War and in his recollections published by his granddaughter, Janet Tucker, she writes that “Lord Kitchener kept pointing to him personally from the posters, telling him his country needed him, but he didn’t need telling; he truly wanted to be a hero, a ‘glory boy’, as he called it. He finally enlisted in November 1915, proud to accept the King’s Shilling and become one of Kitchener’s Army”. (Mud, Blood and Bullets. Memoirs of a Machine Gunner on the Western Front, Spellmount, 2010)

Indeed one Edinburgh lad joined up because the poster “haunted” him and he could not get away from Kitchener’s finger. Similar feelings welled up in young men in the west midlands. Edward Rowbotham was a Black Country veteran of the Great War and in his recollections published by his granddaughter, Janet Tucker, she writes that “Lord Kitchener kept pointing to him personally from the posters, telling him his country needed him, but he didn’t need telling; he truly wanted to be a hero, a ‘glory boy’, as he called it. He finally enlisted in November 1915, proud to accept the King’s Shilling and become one of Kitchener’s Army”. (Mud, Blood and Bullets. Memoirs of a Machine Gunner on the Western Front, Spellmount, 2010)

That New Army, as it was officially called, was the second biggest volunteer army the world had ever seen and most likely will ever see. It drew in almost 2.5 million men from August 1914 until conscription was enacted from March 1916, and as such only the Indian Army in the Second World War had more volunteers.

The driving force behind this New Army was Field Marshal Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War. Soon after the Great War had begun, he realised that it would not be all over by Christmas 1914, as so many believed, and that there was a vital need to raise and train a large force of men quickly to support the regular Army.

This was a small force of just under 250,000 regular troops, all volunteers but almost half of whom were stationed overseas to protect Britain’s imperial and trading interests. To their number could be added several hundred thousand Reservists and Territorial Army volunteers.

Thus, when war broke out in August 1914, and compared to the Germans, French and Russians, the British Army was able to put in the field only a small but highly-trained force of around 80,000 men.

They belonged to the British Expeditionary Force, a new concept. As the twentieth century had dawned the likelihood of war had grown and the formation of the BEF gave the British the ability to intervene swiftly and effectively in a war on the continent. It included six infantry divisions and a cavalry division and was to be placed on the left flank of the French when the need arose. This was to be Flanders – a place which would become iconographic in the British experience of the First World War.

Within days of the declaration of war on August 4, 1914 the BEF had been shipped to France. Derided by the Kaiser as “a contemptible little army”, its doughty troops, helped valiantly by Belgian and French soldiers, held off a much greater German force in Flanders.

The cost was horrendous. Between October 14 and November 30, 1914, the British lost 53,000 men; whilst over 4,500 Indian troops were also killed, wounded or went missing. Reinforcements came from 210,000 Reservists, who made an immense contribution to the British military effort in 1914. Two thirds of these were former regular soldiers and the rest were part of a Special Reserve which had been formed in 1908 from the old Militia.

As for the 269,000 part-time soldiers of the Territorial Army, although they became increasingly important as the war went on, at first they were intended for home defence. Moreover those many who volunteered to fight abroad had to undergo six months’ proper training and receive full equipment before they could be deployed.

Taking all this into account, perhaps 150,000 British troops could be gathered for the battles around Ypres. By contrast the Germans had 1.5 million men on the Western Front. It was clear that the British Army had to grow massively and quickly. Lord Kitchener was fully alert to those imperatives.

As Secretary of State for War, on August 7, 1914 – three days after the declaration of hostilities – he appealed for 100,000 volunteers aged between nineteen and 30 to reinforce the regular Army. He did so through a poster published in newspapers and pasted on walls in prominent places. It was not illustrated but was headed, “Your King and country need you. A Call to Arms.” The response to the “present grave national emergency” was dramatic. Men flocked to the colours and in less than three weeks Kitchener had his men.

On August 28, Kitchener appealed for another 100,000 volunteers and raised the age limit to 35. Again the response was overwhelming. Within two months of the declaration of war 762,000 men had volunteered. This doubled the pre-war strength of the Regular Army, Reservists and Territorials.

By Christmas 1914, one million men had voluntarily signed up to fight for King and Country. It is fashionable today amongst some intellectuals to demean such patriotism. Rightly we condemn the futility of war and we mourn the terrible loss of life, but rightly we should also appreciate the love of their land that motivated so many men to volunteer to fight. Their patriotism sprang up from a deep bond with their street, their neighbourhood, their town, their county. That was their England. They would never let it down and when the call came they did their duty.

Kitchener’s New Army was a major turning point in the history of Britain. For the first time its government and people committed themselves to a massive land force that was supported by a society which was put on to a war footing.

In the months following the outbreak of war, the New Army was faced with severe problems – from a lack of boots and socks to a want of uniforms and barracks; and from a lack of rifles and grenades to a insufficient bayonets and field guns. But as the economy was transformed into one that could fight a total war so too did things improve for the New Army.

Its volunteers joined for three years or the duration of the war, whichever was longer, and were put into ‘Service’ battalions. Each of these was attached to a regular Army regiment. In Birmingham “the rush to the colours” began on August 6, the day before Kitchener made his call for 100,000 men.

In their book ‘Birmingham and the Great War, 1914-1919’, Reginald H. Brazier and Ernest Sandford explained that “the assistance of the police had to be obtained in order to marshal the crowd outside the recruiting headquarters in James Watt Street. The scenes both inside and outside the building were described as being most enthusiastic.”

Lord Kitchener’s appeal quickly added impetus to the movement to volunteer. The Town Hall was opened as a recruiting station and the work of examining and attesting went on seven days a week. By the end of August “several thousands of men had joined the Colours from the city and district”.

The volunteers from Birmingham mostly joined the 9th, 10th and 11th service battalions of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. One of them was my Great Uncle Wal Chinn. At sixteen, and under age, he had tried unsuccessfully to join the Coldstream Guards at Curzon Hall in the city. Undaunted he then went for the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and was accepted. However, my Granddad, who was an Old Contemptible and had been wounded in 1915 and invalided out of the War, found out and turned up at the barracks with his younger brother’s birth certificate.

Great Uncle Wal was then put into a Provisional Battalion with other under age volunteers and ‘old sweats’ and eventually went on to join the 2nd Battalion the Royal Fusiliers. He served on the Western Front in Flanders and saw a lot of action, especially in the Passchendaele Salient. After one skirmish towards the end of the War, he discovered a bullet hole in the flap of his leather jerkin, another through his haversack, and one through the butt of his rifle from the butt trap to the trigger guard.

The men of the 9th (Service) Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment also saw a lot of action as part of the 39th Brigade, 13th Division. In his book ‘The Story of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment’, C. L. Kingsford wrote that the battalion took part in the Gallipoli campaign in Turkey.

The men landed on July 13 and for the next fortnight “served off and on in the trenches, losing their colonel, who was shot by a sniper on July 25”. Two other officers were also killed as were nine men of other ranks.

Soon afterwards, the Battalion took part in the great attack at Anzac Cove. The plan was to capture Koja Chemen (or Hill 971) and the seaward ridges by an advance from Anzac Cove. After the New Zealanders had made ground and had taken Chunuk Bair at the southern end of the main ridge, the actual crest of Koja Chemen was gained by the 9th Royal Warwickshire, led by Major W. A. Gordon, the 6th South Lancashire, and the 6th Gurkhas. The Dardanelles were in sight and victory seemed at hand, but the troops on the right were late, and a Turkish counter-attack forced back the British and Ghurkhas. Kingsford described how “one company of the Royal Warwickshire held on, till they were surrounded, and, as it is supposed, all perished. Next day the Turks attacked in the early morning with disastrous results. The trenches were enfiladed by machine-gun fire, and since no supports were available it was impossible to hold the remainder of the crest on Chunuk Bair.” By evening, when the 9th was withdrawn to reserve, no officers and only 248 men were left.

During the four days of battle, five officers were killed, nine were wounded and one was missing; whilst 57 men were killed, 227 wounded and 117 missing. For their service on these days Majors Gordon and C. C. R. Nevill received the DSO.

A New Zealander who had seen the 1/9th in action “had been struck by their soldierly bearing and, as an old Birmingham man himself, was proud of the imperishable renown which they won”. He declared that:

They had immense difficulties to overcome. They were led the wrong way, and had to retrace their steps; they had to attack in full view of the enemy; their left was exposed to enfilading fire, and, in spite of all, they reached the Rhododendron Spur, and some the very ridge of 971. They held on like grim death, held on when first one and then another unit retired. They asked for reinforcements, but were told none were available, and still they stayed. They were now by themselves, and it was only when every officer save one was killed or wounded that three companies slowly retired. The fourth company, with its gallant major, [Major R. G. Shuttleworth of the Indian Army, who was in command of “A” Company] held on to the farm near the ridge till all were killed. With their ranks terribly thinned they came back as from parade, parched and hungry, but still undaunted.

With so many casualties, the 1/9th Royal Warwickshire was withdrawn to reserve. By September 19 it had received new men and was over 500 strong, and was sent up to trenches near Chocolate Hill. For the next two months, they endured rain, floods, frost, snow and bitter cold– and were unable to light fires or cook food. Thankfully they were evacuated towards the end of December 1915.

One of the most notable features of the local recruitment of volunteers during the Great War was the raising and equipping of the Birmingham City Battalions. Brazier and Sandford noted that there took hold “in Birmingham, as in Liverpool and Manchester, a remarkable demonstration of civic patriotism. The idea of battalions of ‘pals’ which took hold of the two big towns of Lancashire in the latter half of August, germinated in Birmingham almost simultaneously, and with equal success.”

A scheme for the raising of a City Battalion was outlined in a leading article in the ‘Birmingham Daily Post’ on August 28, and the next morning Alderman W. H. Bowater, the Deputy Mayor, sent a telegram to Lord Kitchener stating that “in the absence of the Lord Mayor, who is on military duty, I offer on behalf of the City of Birmingham to raise and equip a battalion of young business men for service in His Majesty’s Army, to be called The Birmingham Battalion. This is in addition to the ordinary recruits who have been enlisted in this city to the number of nearly 8,000.”

So many men responded, that three battalions were actually formed: the 14th, 15th and 16th service battalions. All three were sent to France in November 1915 and by Christmas the 16th was in the front line. During this time, their trenches were heavily bombarded by the enemy. Six men were killed and nine wounded, including Regimental Sergeant-Major Morgan, who later died of his wounds.

Once Kitchener had gained his first 100,000 New Army volunteers, the Territorial Army was then allowed to carry on recruiting for overseas or home service. It was well organised and had popular appeal in Birmingham and Black Country and many men joined it. From September 1914, the Territorials began to free up Regular Army battalions from colonial duties for the war in Europe. They went on to play a vital role – and not only in the Empire.

Early in the war it was agreed that a Territorial Army battalion could be sent to France if 60% of its men volunteered. From late March 1915, all three Territorial battalions of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment from Birmingham had been taken across the English Channel, as part of the Warwickshire Brigade of the South Midland Division Territorial Army Division – later the 143rd Brigade of the 48th (South Midland) Division.

They were the 1/5th and 1/6th based at Thorp Street and the 1/8th based at Aston Cross. Their place at home was taken by second line battalions – hence 2/5th, 2/6th and 2/8th. These latter recruited and trained men for the first line battalions but from 1916 they fought in France as distinct battalions. A third line was formed in the summer of 1915. Finally, men from Handsworth were recruited into the Territorial battalions of the South Staffordshire Regiment, whilst many of those in south-west Birmingham went into the Worcestershire Regiment.

After arriving in France the three Royal Warwickshire Territorial Battalions received training in trench warfare and were then sent to relieve units in the trenches between Ploegsteert and Wulverghem, opposite the Messines Ridge. In this period Lance-Corporal H. Wheeldon of the 1/8th won the Military Medal “for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty displayed at Steenbecque, near Wulverghem, on the night of 19th-20th April 1915, in going, with an officer, to the assistance of Private Holman, who lay mortally wounded close to the enemy and whom they carried in. Lance-Corporal Wheeldon then returned with the officer and searched, without success, for another man who had been shot at the same time.

Two months later, Captain Herbert Davies, also of the 1/8th, was awarded the Military Cross “for conspicuous gallantry and resource on many occasions when on patrol duty in front of the trenches”. The citation in the ‘London Gazette’ went on to add that in particular, “on the night of 20th/21st June 1915 when he carried out a very daring reconnaissance close to the river Douve. From his knowledge of German he obtained very valuable information from the enemy’s conversation after passing over ground lit up by flares and constantly swept by machine-gun fire.”

As for the 1/5th and 1/6th, by July their men were in the Somme country, where and according to the ‘History of the 1/6th Battalion the Royal Warwickshire Regiment’, “on the misty morning of November 4th, a party of the C company were working in front of the wire, when the mist suddenly lifted, and the enemy opened fire”. A man was hit and Lieutenant R.C. Lowe and Sergeant E. Pratt rushed through the wire to bring him in. Lieutenant Lowe was wounded but the two men still managed to bring in their comrade. The office was awarded the Military Cross and Sergeant Pratt the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

The regulars of the 1st Battalion of the Royal Warwicks had remained in the vicinity of Ypres, where it was involved in fierce fighting. On April 25, 1915 the men advanced to support a Canadian unit that had been attacked by gas near to Kitchener Wood. The enemy machine gun fire was heavy and the battalion lost seven officers, with another nine wounded or missing; whilst there were 500 casualties amongst the men.

After reinforcements arrived from England, the 1st moved to the outskirts of Ypres, although some men took part in July attack on Pilkem. During this battle, two lines of enemy trenches were taken, but the Germans then pounded the British with a terrible bombardment. In its midst, an order was given for a machine gun section to get up the line. It seemed impossible to achieve but an officer, sergeant and private did so.

The officer was immediately wounded but under the direction of Sergeant Cresswell, he and Private King fired the machine gun continuously at the Germans. After over two hours in action Sergeant Cresswell spotted enemy reinforcements gathering but because of a British advance trench he was unable to target them. He and Private King then courageously lifted the gun and ran through a hailstorm of bullets to put the gun in position and fire on the Germans. Few of them escaped. The two soldiers of the 1st then picked up their gun and dashed back to safety.

Sergeant Creswell was honoured with the Distinguished Conduct Medal for conspicuous gallantry. The citation declared that he had made “the greatest possible use of his machinegun. The parapet was twice blown in and rebuilt, and he continued with coolness and bravery to serve his gun with good effect”.

However, the first Victoria Cross to be won by a soldier of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment was by Private Arthur Vickers of the 2nd Battalion at the Battle of Loos. On the morning of September 25, 1915, its men forged ahead through withering waves of fire and reached the first German trenches at the Hulloch Quarries.

These were protected by thick barbed wire which had not been cut apart by the British bombardment before the assault. The notice in the ‘London Gazette’ stated that “Private Vickers, on his own initiative and with the utmost bravery, went forward in front of his company under, very heavy shell, rifle and machine-gun fire, and cut the wires which were holding up a great part of the. battalion. Although it was broad daylight at the time he carried out this work standing up. His gallant action contributed largely to the success of the assault.”

That midnight on September 25, the 2nd Royal Warwicks presented themselves for muster. There were no officers left to take their names and out of a total of 523 men who had gone out to battle that morning, only 140 could call out. The rest were dead, wounded or missing in action. Unhappily the battalion was to suffer more grievous losses the next year at the Battle of the Somme.

First published in the Birmingham Mail’s First World War supplement.

-

Hello

What date was this article published?

Thanks,

Bob

Submit a Comment

Comments