Articles

No Comments

By Voices

On 02, Feb 2015 | No Comments | In Commemoration | By Voices

Exhibiting the Great War in 2014

Prof Ian Grosvenor, University of Birmingham

Across Europe and beyond in 2014 the Great War took up residence in museums, art galleries and libraries, with exhibitions presenting the conflict through a national lens.

Exhibitions to be discussed here are Paris 14-18, la guerre au quotidien, a photographic exhibition at the Galerie des bibliothéques de la Ville de Paris, 1914-1918 Der Erste WeltKrieg at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin, and Life Interrupted: Personal Diaries from World War I at the State Library of New South Wales, Australia.

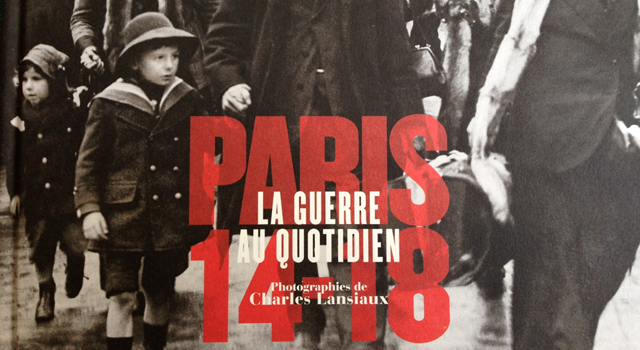

![Paris exhibition catalogue cover [Photo: Ian Grosvenor]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/paris-14-18-1000.jpg) Amongst the earliest exhibitions was Paris 14-18, la guerre au quotidien, a photographic exhibition at the Galerie des bibliothéques de la Ville de Paris which opened in January. The photographs were all taken by Charles Lansiaux and record daily life in the city from the recruitment and departure of French soldiers to victory celebrations in 1918.[1] Walking through the exhibition and viewing the individual photographs was a useful reminder that not only was the First World War a conflict fought in front of the camera lens, it was also the first conflict where the experiences of civilians were extensively visually documented. Further, as publicity for the exhibition noted: ‘La présence récurrente de groupes d’enfants dans ces photographies révèle la place nouvelle qui leur incombe, à l’aube du XXe siècle’. Children are ‘caught’ watching military parades and adopting military poses, Boy Scouts march with along with soldiers, and children are photographed in family groups alongside their fathers in military uniform. Domestic images of children playing in parks, shopping and being entertained by street vendors are displayed next to photographs of child refugees and their families arriving from Belgium and children queuing in soup kitchens. A photograph of a hospitalized child injured in a bomb attack is followed by images of children looking at bomb damage on the street. Child newspaper sellers distribute news reports of events on the Western Front, while others sell patriotic medals or are photographed collecting donations for war orphans and refugees. Children, their heads uncovered, observe the ‘spectacle’ of a military funeral cortege while other children are photographed looking at artillery, sitting astride large canons and parading on Armistice Day. It is obvious that a large number of Lansiaux’s photographs were staged; nevertheless they collectively reveal the multiple contingencies which informed and controlled civilian experiences of war time conditions.

Amongst the earliest exhibitions was Paris 14-18, la guerre au quotidien, a photographic exhibition at the Galerie des bibliothéques de la Ville de Paris which opened in January. The photographs were all taken by Charles Lansiaux and record daily life in the city from the recruitment and departure of French soldiers to victory celebrations in 1918.[1] Walking through the exhibition and viewing the individual photographs was a useful reminder that not only was the First World War a conflict fought in front of the camera lens, it was also the first conflict where the experiences of civilians were extensively visually documented. Further, as publicity for the exhibition noted: ‘La présence récurrente de groupes d’enfants dans ces photographies révèle la place nouvelle qui leur incombe, à l’aube du XXe siècle’. Children are ‘caught’ watching military parades and adopting military poses, Boy Scouts march with along with soldiers, and children are photographed in family groups alongside their fathers in military uniform. Domestic images of children playing in parks, shopping and being entertained by street vendors are displayed next to photographs of child refugees and their families arriving from Belgium and children queuing in soup kitchens. A photograph of a hospitalized child injured in a bomb attack is followed by images of children looking at bomb damage on the street. Child newspaper sellers distribute news reports of events on the Western Front, while others sell patriotic medals or are photographed collecting donations for war orphans and refugees. Children, their heads uncovered, observe the ‘spectacle’ of a military funeral cortege while other children are photographed looking at artillery, sitting astride large canons and parading on Armistice Day. It is obvious that a large number of Lansiaux’s photographs were staged; nevertheless they collectively reveal the multiple contingencies which informed and controlled civilian experiences of war time conditions.

![Polish civilians registered by German occupiers, 1916/17 [Deutsches Historisches Museum]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/dhm-exhibit-1000.jpg) 1914-1918 Der Erste WeltKrieg at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin[2], which opened a few months later, took a more panoramic view of the war drawing on archives from across Europe. The exhibition was organised around fourteen places as points of departure, including battlefields (Verdun, Tannenburg and Gallipoli), political-cultural centres (Petrograd and Berlin) and occupied cities and regions Brussels and Galicia). It began with a display of objects demonstrating the close links between the British and German royal families, evidence of German industrial power and European rivalry in terms of colonial expansion and the armament race. The issue of what was the cause of the war was not directly addressed, although it was suggested that political allegiances made it almost inevitable. However, in a later section of the exhibition it was acknowledged that with the invasion of Belgium Germany lost the worldwide debate about who caused the war. What was one of the striking features of Der Erste WeltKrieg was its focus on documenting the impact of German expansion on local populations. The story of the Belgian refugee crisis is well known, but less so that of the 60,000 Belgians who were used as forced labour by 1916 and transported to Germany. At the same time, the haemorrhaging of refugees fleeing occupation led to the installation of an electrified fence, built by forced labour and paid for by Belgian citizens. The extent of Belgian resistance and patriotism surprised the German army and one soldier, Harry Graf Kessler, recorded in his diary the summary execution of Belgian civilians for attacking German soldiers. But he was also appalled by the misery that the German occupation caused. Another soldier, Willy Jackel, captured the horrors of war including sexual violence in a series of drawings. The experiences of Armenian refugees and Polish forced labour presented in the exhibition further demonstrated the devastating impact of the war on civilians.

1914-1918 Der Erste WeltKrieg at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin[2], which opened a few months later, took a more panoramic view of the war drawing on archives from across Europe. The exhibition was organised around fourteen places as points of departure, including battlefields (Verdun, Tannenburg and Gallipoli), political-cultural centres (Petrograd and Berlin) and occupied cities and regions Brussels and Galicia). It began with a display of objects demonstrating the close links between the British and German royal families, evidence of German industrial power and European rivalry in terms of colonial expansion and the armament race. The issue of what was the cause of the war was not directly addressed, although it was suggested that political allegiances made it almost inevitable. However, in a later section of the exhibition it was acknowledged that with the invasion of Belgium Germany lost the worldwide debate about who caused the war. What was one of the striking features of Der Erste WeltKrieg was its focus on documenting the impact of German expansion on local populations. The story of the Belgian refugee crisis is well known, but less so that of the 60,000 Belgians who were used as forced labour by 1916 and transported to Germany. At the same time, the haemorrhaging of refugees fleeing occupation led to the installation of an electrified fence, built by forced labour and paid for by Belgian citizens. The extent of Belgian resistance and patriotism surprised the German army and one soldier, Harry Graf Kessler, recorded in his diary the summary execution of Belgian civilians for attacking German soldiers. But he was also appalled by the misery that the German occupation caused. Another soldier, Willy Jackel, captured the horrors of war including sexual violence in a series of drawings. The experiences of Armenian refugees and Polish forced labour presented in the exhibition further demonstrated the devastating impact of the war on civilians.

Victory on the battlefield resulted in Prisoner of War Camps which became a ‘laboratory’ for German ethnologists, philologists and musicologists to study popular culture. Captive African and Asian soldiers were a source of public curiosity and paintings were commissioned to capture the likeness of the ‘other.’ Newspaper in vernacular languages were produced to try and persuade imprisoned Muslim soldiers to change sides. Prisoners were categorised by religion and place of origin but also reflected ‘race’ hierarchies with Russian and Colonial soldiers being lesser beings than English and French prisoners and their conditions and treatment in the camps reflected accordingly. Indeed, it was clear from the exhibition that the further eastward in Europe the Germans advanced the more their prejudices about Eastern Europeans were reinforced. The exhibition also pointed to contradictions within Germany itself with, on the one hand, each German army having a rabbi to meet the pastoral needs of Jewish soldiers and, on the other, the compiling of a Jewish census in 1916 because of a widespread belief that the German Jewish population were not pulling their weight which, in turn, fuelled anti-Semitism.

The propaganda war generated by both sides in the conflict as presented in the exhibition suggests that the demonization of the enemy while central to allied propaganda was largely absent from that in circulation in Germany. Another common experience associated with the conflict again drawing on the visual archives of both sides is that of the physical destruction of the human body. Front-line dismemberment and the provision of artificial limbs, facial disfigurement and reconstruction affected friend and foe alike. Silent films of soldiers traumatised by the conflict, their bodies shaking continuously, were shocking to see, but left an almost voyeuristic imprint on the retina. Battlefield photographs showing the deaths of comrades were forbidden by the German censor and yet here they were on display, images from Ypres which were circulated, reproduced and sent home.

The exhibition was perhaps weakest in presenting life on the home front. Other than some fascinating photographs of German citizens waiting to hear about the declaration of war and an image of a domestic interior showing a mother and child wearing gas masks the exhibition was largely silent on the civilian experience of war until near the end in a section called Berlin: the Exhausted Metropolis. Here statistics were presented (child mortality rates increasing by over 50% from 1914 and twice as many mothers dying in childbirth than in 1914) and evidence displayed of food shortages (becoming acute by 1916), and increase levels of prostitution, venereal disease, and crimes against property. Silent films captured the feel of the exhausted city and allowed the visitor to observe the distress associated with food shortages. In one film children are caught slowly and deliberately spooning food into their mouths while staring straight into the camera lens. Such a staged image is similar to those constructed by Lansiaux, but unlike the Paris exhibition, the effect of the war in particular on children was limited to these few images and statistics. The only other view of the child was in an earlier section where two of some 1500 drawings produced by Moscow school children captured the impact of the war on their daily lives.[3]

![War diaries on display in Sydney [Photo: Ian Grosvenor]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/state-library-nsw-1000.jpg) The final exhibition to be discussed here is Life Interrupted: Personal Diaries from World War I which opened at the State Library of New South Wales in July 2014.[4] The exhibition was constructed around the content found in a magnificent collection of personal diaries held by the Library. Collecting the diaries began before the war ended. In the aftermath of Gallipoli the Principal Librarian, Willam Ifould, recognising the importance of first-hand testimony placed advertisements in Australian and British newspapers offering to buy diaries and original letters. By 1921 the number of diaries in the library reached 247 and had been written by soldiers, doctors, nurses, stretcher-bearers and journalists. They were complemented by collections of letters and photographic albums. Life Interrupted is a fitting title for the exhibition which for many soldier diarists began as a ‘big adventure’ as they signed up for a ‘Free Tour to Great Britain and Europe. The ‘Chance of a Lifetime’ as one recruitment poster stated, soon turned into tragedy. Using the diaries the exhibition followed the chronology of the war for Australians: recruitment and training, the campaign in German New Guinea, the pursuit and sinking of the German cruiser Emden, the long boat journey to Egypt, then Gallipoli, the Western Front and the Middle East campaign, incarceration as prisoners of war, Victory, Peace and new traditions of public mourning. Using the words of these wartime chroniclers the exhibition reflected the enormity of the conflict, but also its impact on the nation. The diary entries represent a conversation with home.

The final exhibition to be discussed here is Life Interrupted: Personal Diaries from World War I which opened at the State Library of New South Wales in July 2014.[4] The exhibition was constructed around the content found in a magnificent collection of personal diaries held by the Library. Collecting the diaries began before the war ended. In the aftermath of Gallipoli the Principal Librarian, Willam Ifould, recognising the importance of first-hand testimony placed advertisements in Australian and British newspapers offering to buy diaries and original letters. By 1921 the number of diaries in the library reached 247 and had been written by soldiers, doctors, nurses, stretcher-bearers and journalists. They were complemented by collections of letters and photographic albums. Life Interrupted is a fitting title for the exhibition which for many soldier diarists began as a ‘big adventure’ as they signed up for a ‘Free Tour to Great Britain and Europe. The ‘Chance of a Lifetime’ as one recruitment poster stated, soon turned into tragedy. Using the diaries the exhibition followed the chronology of the war for Australians: recruitment and training, the campaign in German New Guinea, the pursuit and sinking of the German cruiser Emden, the long boat journey to Egypt, then Gallipoli, the Western Front and the Middle East campaign, incarceration as prisoners of war, Victory, Peace and new traditions of public mourning. Using the words of these wartime chroniclers the exhibition reflected the enormity of the conflict, but also its impact on the nation. The diary entries represent a conversation with home.

2014 saw many examples of events marking the Centenary and more are planned for subsequent years. These three exhibitions presented different national perspectives on a global conflict. None of them glorified. There was no winner in the stories they told, but each of them through the interpretation of the curators enriched our understanding of lives interrupted by the conflict. Each of them went some way to address the challenge posed by the Palestinian intellectual Edward Said in one of his final essays where he promoted the idea of ‘communities of interpretation’ as a rejoinder to the ‘terrible reductive conflicts’ that herd people under falsely unifying rubrics and invent collective identities for large numbers of individuals who are actually very diverse. For Said, these ‘communities of interpretation’ would investigate, analyse, apprehend, criticize and judge in a mission of understanding.[5] If there is to be one achievement of this period of commemoration it should be that of sharing understanding across national boundaries.

[1] The exhibition was open 15 January 2014 -15 June 2014. All of the images are reproduced in Marie-Brigitte Metteau (ed.) Paris 14-18, la guerre au quotidien. Photographies de Charles Lansiaux (Paris: Bibliotheques de la Ville de Paris, 2014)

[2] The exhibition was open 29 May-30 November 2014. There is an accompanying book but it is only available in German: Der Erste Weltkrieg in 100 Objeckten (Berlin: Deutsches Historisches Museum, 2014)

[3] The drawings were exhibited in Moscow as early as January 1915, see Evgeny Lukyanov, ‘The Great War through the eyes of children: a collection of children’s paintings from the First World War’, Views. War and Peace, 51, Autumn 2014, 46-47.

[4] The exhibition was open 5 July-21 September and the exhibition guide can be downloaded from www.sl.nsw.gov.au/events/exhibitions/2014/life_interrupted/index.html

[5] Edward Said, ‘Preface’ in Orientalism (London: Peregrine Books, 2003)

Submit a Comment