Articles

No Comments

By Voices

On 07, Mar 2014 | No Comments | In Belief | By Voices

Joseph Southall and Pacifism

Martin Killeen, Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham

www.suburbanbirmingham.org.uk

Joseph Southall was born into a Nottingham Quaker family in 1861; on the death of his father the following year his mother brought him to Birmingham. He first learned to paint at the Friends’ School in Yorkshire, before joining the Birmingham firm of architects, Martin and Chamberlain, which he left in 1882 to attend the Birmingham School of Art. Here he met A.J. Gaskin and became one of the emerging Birmingham Group, an important school of artists heavily influenced by Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris and John Ruskin.

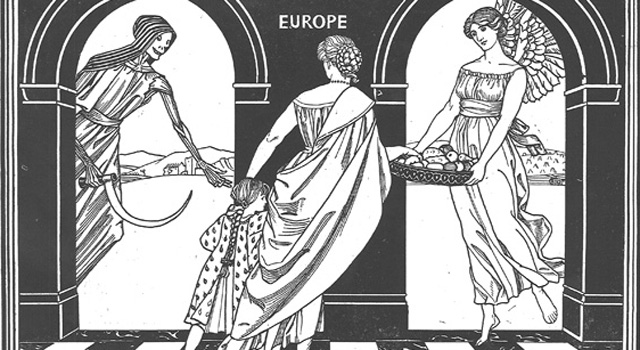

!['Peace or Famine' by J. Southall, 1917 [© Reproduced with permission of the Barrow Family. University of Birmingham: rfJN 976.W66]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/europe-peace-or-famine.jpg) In the 1880s Southall moved into a property belonging to his uncle, George Baker, at 13 Charlotte Road, Edgbaston, which became his lifelong home. During this period he toured Italy, where he studied the work of the early masters; this inspired his experiments with tempera, a technique in which he led a significant revival. In 1903 he married Anne Baker his first cousin, while his reputation as an artist reached its peak of international success at his exhibition at the Galeries Georges Petit in Paris in 1910.

In the 1880s Southall moved into a property belonging to his uncle, George Baker, at 13 Charlotte Road, Edgbaston, which became his lifelong home. During this period he toured Italy, where he studied the work of the early masters; this inspired his experiments with tempera, a technique in which he led a significant revival. In 1903 he married Anne Baker his first cousin, while his reputation as an artist reached its peak of international success at his exhibition at the Galeries Georges Petit in Paris in 1910.

Throughout his life Southall was a leading figure in Birmingham Quaker life as a committed Socialist and radical activist. When the European conflict broke out in 1914 he diverted most of his energies into pacifism. He dropped his allegiance to the Liberal Party and immediately joined the Independent Labour Party, becoming Chairman of the Birmingham City Branch; the ILP was the one left-wing body that consistently maintained its opposition to the war. He also chaired the Birmingham Auxiliary of the Peace Society and was a joint Vice-president of the Birmingham and District Passive Resistance League.

![Sketch for Peace by Joseph Southall Sketch for Peace by Joseph Southall, 1937 [© Reproduced with permission of the Barrow Family. Birmingham Museums Trust: 1981P71]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/1981-p71.jpg) Despite his outspoken stance against the war, he was commissioned by the City to produce the fresco that stands at the head of the stair-case of the entrance to Birmingham Art Gallery. ‘Corporation Street, Birmingham in March 1914’ conveys its pro-peace politics by implication, providing the population with an image of their recent pre-war community life. He also painted ‘The Return of Peace’, one of the huge murals for the Hall of Heroes presented at the 1916 Royal Academy Arts and Crafts Exhibition in London. This national patriotic celebration included work by two other members of the Birmingham Group, Henry Payne and Charles Gere. Only Payne’s original mural survives; Southall’s designs and studies for this work show that his canvas was over twenty feet high and consisted of a family in modem dress below an angel bearing the fruits of peace. However, during this period the artist’s pronounced antiwar views found their most powerful expression in the series of illustrations that were published in radical newspapers and pamphlets.

Despite his outspoken stance against the war, he was commissioned by the City to produce the fresco that stands at the head of the stair-case of the entrance to Birmingham Art Gallery. ‘Corporation Street, Birmingham in March 1914’ conveys its pro-peace politics by implication, providing the population with an image of their recent pre-war community life. He also painted ‘The Return of Peace’, one of the huge murals for the Hall of Heroes presented at the 1916 Royal Academy Arts and Crafts Exhibition in London. This national patriotic celebration included work by two other members of the Birmingham Group, Henry Payne and Charles Gere. Only Payne’s original mural survives; Southall’s designs and studies for this work show that his canvas was over twenty feet high and consisted of a family in modem dress below an angel bearing the fruits of peace. However, during this period the artist’s pronounced antiwar views found their most powerful expression in the series of illustrations that were published in radical newspapers and pamphlets.

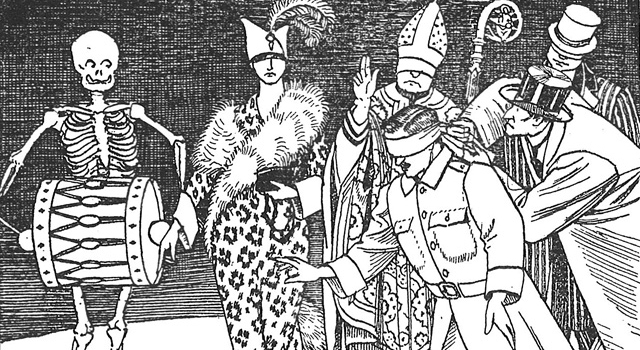

The antiwar pamphlet Ghosts of the Slain, with illustrations by Joseph Southall, was written by Robert Leonard Outhwaite, a farmer and one-time Liberal MP who became a fellow member of the Independent Labour Party. Whilst most of Southall’s wartime energies were consumed by pacifist activism in Birmingham, his artistic output found a new outlet in print caricature.

![Ghosts of the Slain, illustrated by J. Southall, 1915 [© Reproduced with permission of the Barrow Family. University of Birmingham: rpqD525.098]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/vwp-southall-ghosts-04.jpg) Outhwaite’s text offers a clear message of Christian pacifism, expressed in a Biblical style, which provides Southall with an ideal opportunity to articulate his own ideology. Southall’s draughtsmanship might lack the savagery which characterizes much First World War protest in print caricature, but nevertheless his work communicates the same embittered passions and he encapsulates his meaning with a confidence and clarity of purpose, expertly using simple techniques to often startling effect.

Outhwaite’s text offers a clear message of Christian pacifism, expressed in a Biblical style, which provides Southall with an ideal opportunity to articulate his own ideology. Southall’s draughtsmanship might lack the savagery which characterizes much First World War protest in print caricature, but nevertheless his work communicates the same embittered passions and he encapsulates his meaning with a confidence and clarity of purpose, expertly using simple techniques to often startling effect.

The first illustration depicts ‘all those who sit in the high places and cast the people into the pit’. A diplomat and a businessman push a blindfolded officer towards a precipice, whilst a fashionable society woman looks on and a cleric of the Established Church appears as the priest who ‘blessed our banners and bade speed to our swords’. Apart from Death, who gleefully accompanies this performance on his drum, only the diplomat sees what is happening; the others all have their eyes covered.

‘The Obliterator’ appeared in his anti-war pamphlet Fables and Illustrations opposite a mock sales promotion advertising the Obliterator’s record of leaving ‘nothing standing and nothing breathing’ while making ‘a clean sweep of civilisation’. Southall’s woodcuts and satirical fables were published when most of his wartime energies were consumed by pacifist activism in Birmingham and print caricature provided him a convenient alternative artistic output. The essence of his moral standpoint is an unshakable absolute conviction of conscience, clearly articulated in his fable ‘Inscription from Babylon’: although citizens ‘ought to be law-abiding’, in the final analysis, pacifism is justified by faith that ‘Divine law stood above human laws’ in the form of the the sixth Commandment: ‘Thou shalt not kill’.

![Fables and Illustrations, by Joseph Southall Fables and Illustrations, by J. Southall, 1918 [© Reproduced with permission of the Barrow Family. Birmingham Museums Trust: 1978P198]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/1978-p198-11.jpg) Southall’s satire in Fables and Illustrations also ties in with his involvement in local and national politics, allowing his pen to express challenging views in both image and text. In this way he could counter the pro-war propaganda of the ‘priests of Jingo’ and ‘the ruling classes of Europe’. For example, an issue that particularly engaged Southall in 1917 was the imprisonment of his Quaker friend the outspoken pacifist politician Edmund Morel. As secretary of the Birmingham Branch of the ILP he moved a resolution to lobby the Prime Minister and Home Secretary in protest. Although he is not named, Morel’s cause is pursued in ‘The Earth and the Moon’. In this fable politicians invent pretexts and contrive imaginary threats to justify and escalate war, while truth-telling pacifists oppose lying warmongers (‘magicians’):

Southall’s satire in Fables and Illustrations also ties in with his involvement in local and national politics, allowing his pen to express challenging views in both image and text. In this way he could counter the pro-war propaganda of the ‘priests of Jingo’ and ‘the ruling classes of Europe’. For example, an issue that particularly engaged Southall in 1917 was the imprisonment of his Quaker friend the outspoken pacifist politician Edmund Morel. As secretary of the Birmingham Branch of the ILP he moved a resolution to lobby the Prime Minister and Home Secretary in protest. Although he is not named, Morel’s cause is pursued in ‘The Earth and the Moon’. In this fable politicians invent pretexts and contrive imaginary threats to justify and escalate war, while truth-telling pacifists oppose lying warmongers (‘magicians’):

‘One of the most distinguished Imperians [Morel] even went so far as to publish a treatise [‘Truth and the war’ (1916)], in which he proved by theory and experiment that the real danger lay not in any attack from the moon but from the errors and greed of the magicians. This disloyal person was at once cast into prison.’

This is an extract from www.suburbanbirmingham.org.uk

![Fables and Illustrations, by J. Southall, 1918 [© with permission of the Barrow Family. Birmingham Museums Trust: 1978P198] Fables and Illustrations, by J. Southall, 1918 [© with permission of the Barrow Family. Birmingham Museums Trust: 1978P198]](https://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/the-obliterator.jpg)

Submit a Comment