Articles

2 Comments

By Voices

On 16, Sep 2015 | 2 Comments | In Gender | By Voices

Women Doctors in the First World War

Dr Martha Jane Moody Stewart in Worcester and Beyond

Dr Rebecca Wynter, University of Birmingham

Dr Martha Jane Moody Stewart was in 1915 the first female House Surgeon at Worcester Infirmary. Local records seemed to offer little more to the Worcestershire World War 100 (WWW100) volunteer researchers. They found she had graduated from Queen’s University, Belfast, and that she left Worcester soon after arriving. An old local history book implied (rather bluntly) that in wartime circumstances the hospital was ‘forced’ to employ a woman doctor, but made no mention as to the reasons for her swift departure.

![A party of Mabel St Clair Stobart's medical staff leaving for First World War service [Wellcome Library, London. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/medical-staff-wellcome-cc-by-nc-nd-4-460x310.jpg) Curiosity about this ground-breaking female physician was piqued, and Worcester’s George Marshall Medical Museum and The Infirmary Museum, along with their other WWW100 partners (including the University of Worcester), set about seeking someone to research her story and help develop her place in exhibitions at the museums.

Curiosity about this ground-breaking female physician was piqued, and Worcester’s George Marshall Medical Museum and The Infirmary Museum, along with their other WWW100 partners (including the University of Worcester), set about seeking someone to research her story and help develop her place in exhibitions at the museums.

It was at this point that I joined the project. I am a historian of medicine, and over the past two-and-a-half years, my research has taken me into deeper explorations of medical care during the First World War. Work on the Friends’ Ambulance Unit has led me recently to co-curate ‘Faith & Action: Quakers & the First World War’ at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. I have also just completed a Visiting Research Fellowship at John Rylands Research Institute (University of Manchester). Here, I worked on the papers of Geoffrey Jefferson, a pioneering neurosurgeon whose wartime work had taken him between Manchester and the Eastern and Western Fronts. Research on Stewart is a natural progression, and I am delighted to be working with colleagues at Worcester in sharing with people a hidden aspect of the 1914/18 conflict.

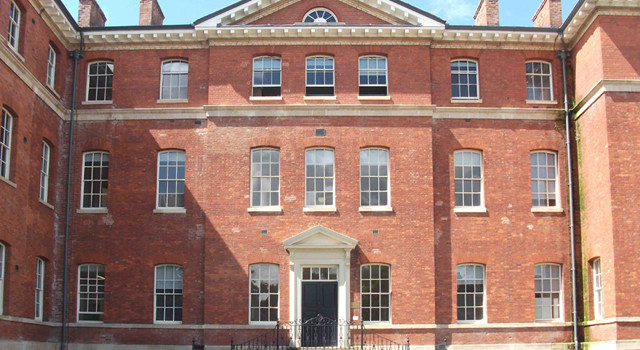

![Former Worcester Royal Infirmary, today home to City Campus, University of Worcester [©University of Worcester]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/worcester-royal-infirmary-university-of-worcester-460x310.jpg) I have already begun to unearth more of Stewart’s story. Worcester was, only a few weeks after her graduation, Stewart’s first appointment and seems to have been a key stepping stone in her medical career. After leaving the Infirmary in mid-1915, Stewart joined the Serbian Relief Fund (SRF) and headed to the crucible of the hostilities. Under the direction of Mabel St Clair Stobart, with an overwhelmingly female staff, and from the hospital base in Kragujevatz (Serbia’s ‘second city’), a series of dispensaries was established in outlying areas, one of which was run by Stewart. Within weeks the Serbian army collapsed and she, other voluntary medical staff, and Serb forces were fleeing for their lives. Most of the SRF made it back to Britain by December. Soon after, in 1916, the British authorities finally accepted that female physicians were needed and useful. Even then, they were permitted only to work as civilians attached to Royal Army Medical Corp (RAMC) units, often in ‘quieter’ locations. It was at this point that Stewart seems to have joined the RAMC and thrived, serving in Malta, then Salonika, before leaving just before the war ended in 1918.

I have already begun to unearth more of Stewart’s story. Worcester was, only a few weeks after her graduation, Stewart’s first appointment and seems to have been a key stepping stone in her medical career. After leaving the Infirmary in mid-1915, Stewart joined the Serbian Relief Fund (SRF) and headed to the crucible of the hostilities. Under the direction of Mabel St Clair Stobart, with an overwhelmingly female staff, and from the hospital base in Kragujevatz (Serbia’s ‘second city’), a series of dispensaries was established in outlying areas, one of which was run by Stewart. Within weeks the Serbian army collapsed and she, other voluntary medical staff, and Serb forces were fleeing for their lives. Most of the SRF made it back to Britain by December. Soon after, in 1916, the British authorities finally accepted that female physicians were needed and useful. Even then, they were permitted only to work as civilians attached to Royal Army Medical Corp (RAMC) units, often in ‘quieter’ locations. It was at this point that Stewart seems to have joined the RAMC and thrived, serving in Malta, then Salonika, before leaving just before the war ended in 1918.

So we now have a clearer idea of the broad framework of Stewart’s war and how Worcester fitted in. But why did she leave the Infirmary? What did she look like? What were her experiences abroad? What exactly happened next? These are questions that will dominate the coming months. Then, through the exhibitions, Martha will finally return to Worcester, where hopefully she will this time stay.

If you have any further information about Dr Martha Jane Moody Stewart, Dr Wynter would be pleased to hear from you: r.i.wynter@bham.ac.uk.

Images:

A party of Mabel St Clair Stobart’s medical staff leaving for First World War Service. Wellcome Library, London. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Former Worcester Infirmary, today home to City Campus, University of Worcester ©University of Worcester

-

I have passed this on to Caroline Magnus who has followed up a Shropshire nurse who was also in Serbia. I have asked if she came across any references to your woman in her research.

-

Caroline responds:

I’m showing off – I think this refers to her while working in Serbia! No doubt they have already found this. She was in a different organisation from the 2 Alices.The dispensary at Rekovatz was started on September 4th. The camp was as usual installed, and in working order, by the evening. The dispensary, in four little rooms in a cottage at the entrance to the garden, and the staff in tents. Dr. Stewart was an ideal woman for the work. In addition to professional skill, she had a keen sense of humour, patience and enthusiasm, and she soon established a success. She was sent for the first evening to see a woman who was too ill to leave her bed. The patient, in a two-roomed cottage, was lying in a tiny room, without any sign of ventilation, past or present. She was closely surrounded by friends; they had already put into her hand the lighted candle—token that she was to die. The doctor opened the window, forced a passage to the bedside through the mourners, gently ousted them, and took stock of the patient. Double pneumonia was the verdict. But there was no reason, except the expressed determination of the relatives, why death should result, if only fresh air, and food, and medicines, at regular intervals, could be assured. It seemed almost a pity to rob the friends of their intended tragedy, but the doctor removed the candle from the victim’s hands, and said that there was no reason why the woman should not live; but orders must be obeyed. “Who was in charge?” The mother came forward. “Very well, now you must see (through the interpreter) that your daughter takes the medicine, which I will send, every four hours. Do you understand?”

“Yes, but how are we to know when it is four hours?” “Have you no clocks or watches?”

“None.”

“And none in the village?”

“No!”

“Very well, then you must give the medicine every time you eat your meals.”

“We only eat three times a day.”

“Then give the medicine three times regularly, and do everything that I tell you, and she’ll get better.”

The friends in chorus promised that if she got better they would give the doctor a pig—a fat pig. The fat pig was earned, and many other pigs, and fruits, and presents of all kinds were received by the doctor and her staff from grateful patients.

Comments